How do Fireflies glow?

Test English

Table of Contents

Sadly these dazzling beetles and their famous lights are vanishing all around our planet. This is due to loss of their natural habitat, pesticides and light pollution. I am quite saddened by this thought, as they and especially their ability to glow was always something that kept me amazed and bewildered when I was small. Even though there is less magic involved than the little me thought, the actual chemical process is still a very magical one: Bioluminescence - The production and emission of light by living organisms.

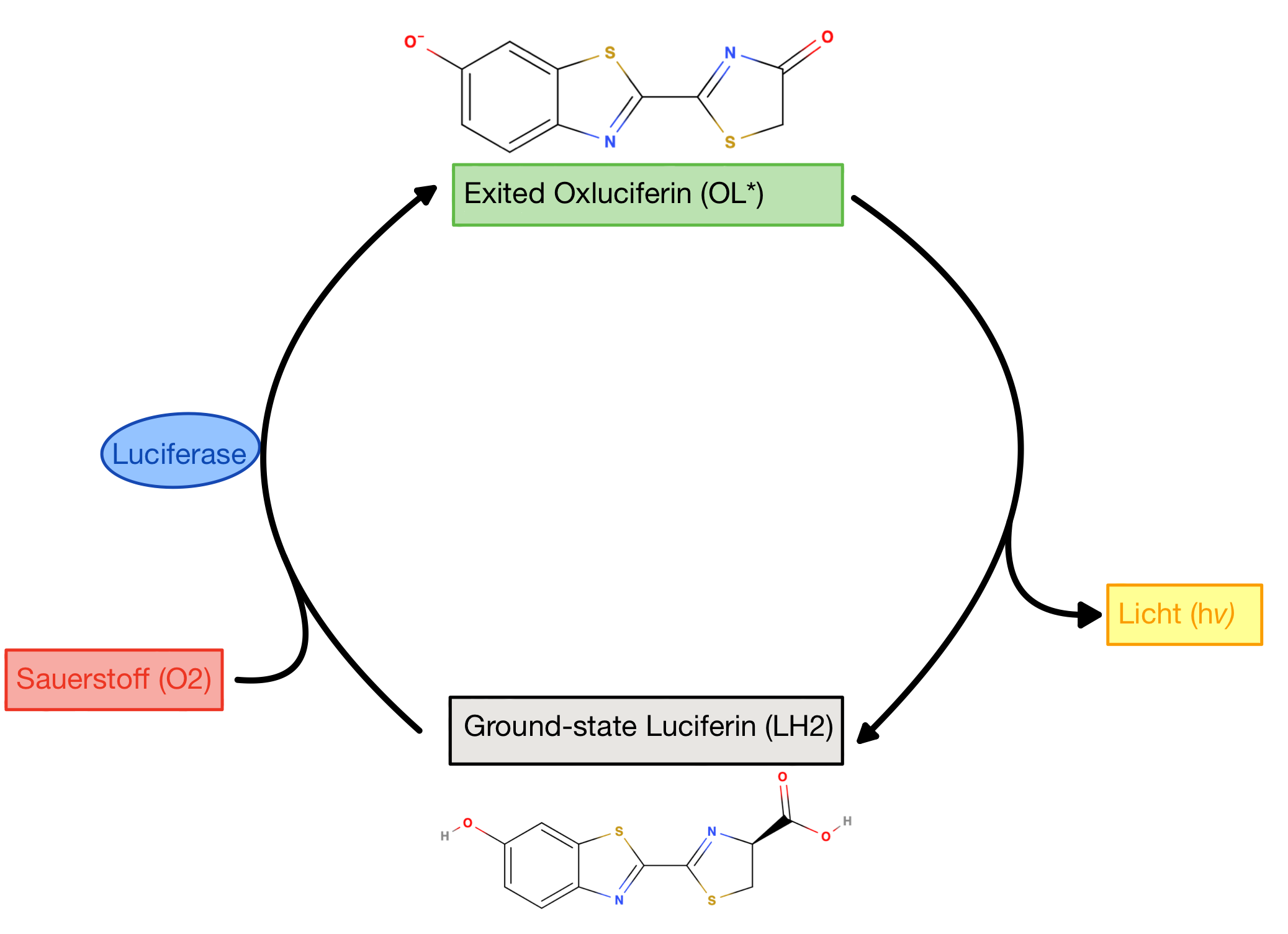

Fireflies are the most well-known and studied bioluminescent organisms. Responsible for the light production is a special enzyme-substrate system: The firefly Luciferase (enzyme) and the Luciferin (substrate). Enzymes are Proteins that act as a catalyst in biological reactions: They accelerate them but do not alter them. The molecule they are converting is called the substrate. The enzyme catalyses the conversion of firefly Luciferin into an oxidized excited state. Excited state in chemistry means that electrons moved to a higher energy level, or in other words further away from the nucleus (the positive charged centre of the atom). You can read more about excitation here. When it returns to the ground state Energy in form of light is released [1]. (Fig.1) provides a high-level depiction of this process.

It appears that the glowing itself has several purposes: In larvae it functions as a warning sign for predators to communicate their distastefulness. In adults, many different glow patterns are observed. These different patterns serve to differentiate between species, as well as for mating purposes [2]. Interestingly, there is also a dark side to their light communication: Sometimes the females of certain species emit light to lure in males in order to eat them up. They do so by imitating the flash sequence of females of another species, which then attracts the males of that species [3].

The structures of Luciferase and Luciferin

Luciferase

The protein structure consists of two compact domains: a larger N-terminal domain and a smaller C-terminal domain linked through a flexible linker peptide. Feel free to explore this in (Fig.2) above. And for more background knowledge about Aminoacids and Protein feel free to explore here.(TODO) Luciferase is part of the adenylate forming (see below in the 1st reaction equation) superfamily of enzymes. In this superfamily, the amino acids of the two domains that face each other in the cleft are conserved. What does conserved mean? Nucleic acid (DNA/RNA) sequences or like in this case and Aminoacid sequence can be identical or similar across species or within a genome. These sequences are called conserved sequences. These sequences have been maintained through evolution by natural selection. The conservation is a strong pointer that the cleft is the active site of the protein where the actual catalytic reaction takes place. The cleft (as you can see in the model) seems far too big for simultaneous interactions between the residues on both sides and the substrates. Hence, it is suggested that both domains undergo a conformational change and close the substrate in like a sandwich. A conformational change describes the process of a protein changing its shape. In this case, in order to fit the substrate. This would provide the perfect conditions for the reaction: Water is excluded and cannot react with the Adenosinetriphosphate (ATP) nor the excited-state product. But where and how exactly it works is yet to be determined [2].

Luciferin

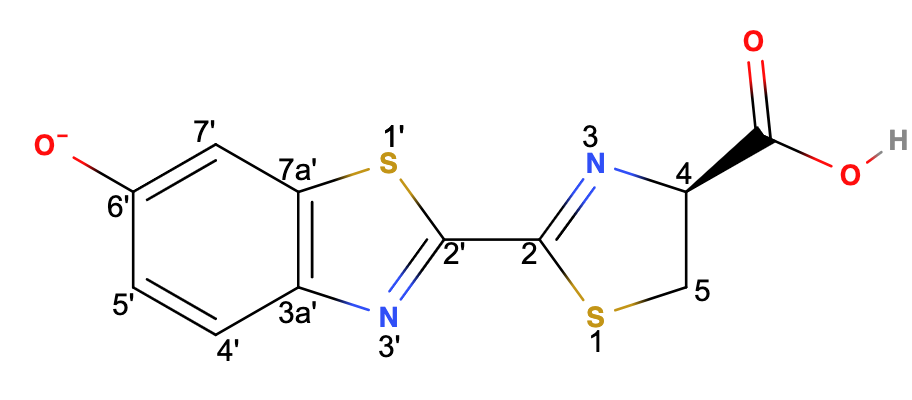

As shown in (Fig.3) above, the firefly luciferin (

Mechanism Overview

The chemical reaction can roughly be divided into two steps:

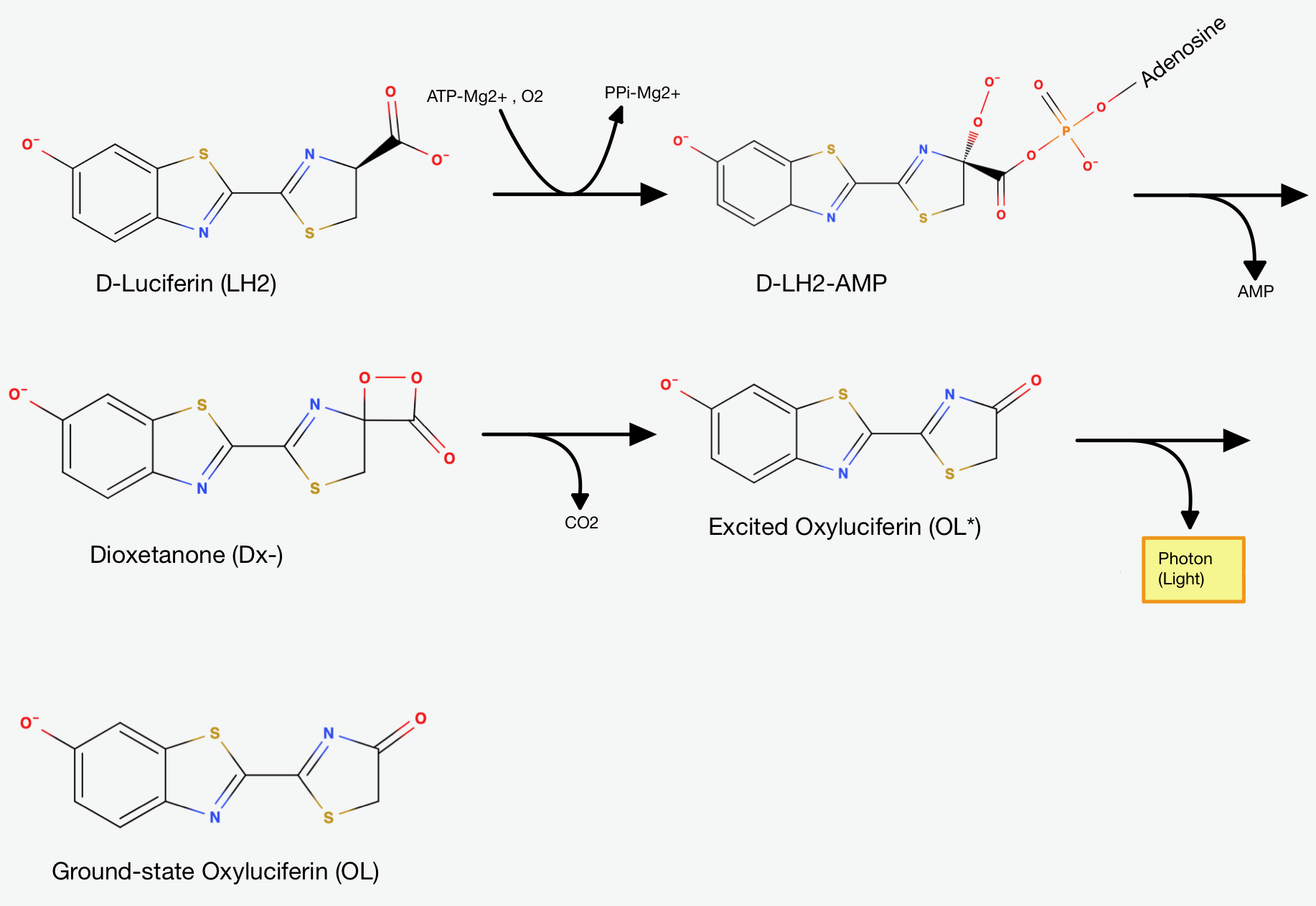

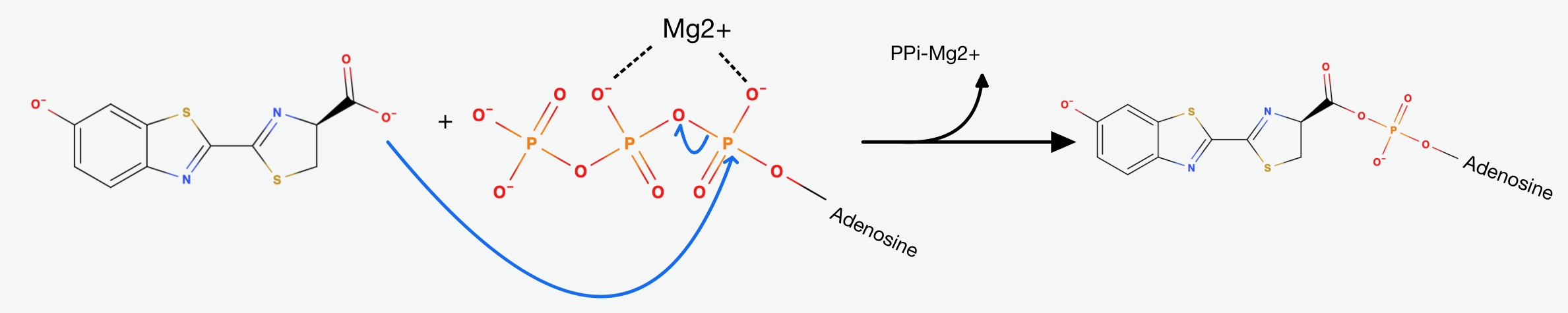

In the first step, the firefly Luciferase catalyses the reaction of Luciferin(

The Luciferyl adenylate then undergoes oxidation - it reacts with oxygen - and cyclization (the formation of one or more rings in the chemical compound). The resulting product is Dioxetanone. The decomposition of the Dioxetanone intermediate is the essential part for light emission.

How exactly the Dioxetanone gets decomposed is still a subject of debate, as there are multiple mechanisms suggested. Generally, it's suggested

that the Dioxetanone undergoes a decarboxylation reaction - a reaction where the Carboxylgroup (

If the description until now kept you on the edge of your seat... there is the full mechanism broken down in more detail for you ahead. The detailed description will assume some knowledge about the basics of organic chemistry. But even if there are some holes in your knwoledge about organic chemistry, it is worth taking a look. For more in depth explanations about the chemistry you can take a peek into the OC section here(TODO).

In-Depth Discussion of the Mechanism

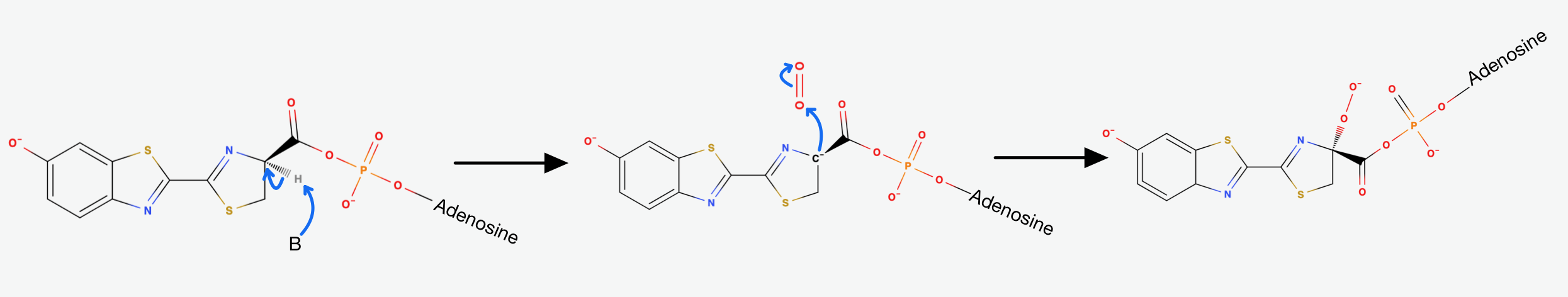

The first step is the adenylation step. The luciferase catalyses a

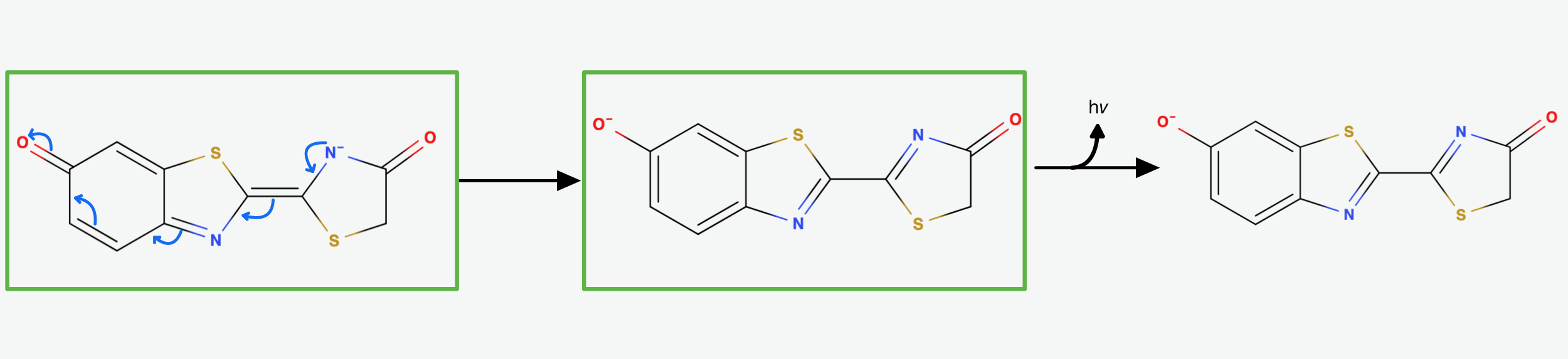

The presence of AMP substantially increases the acidity of the proton on Carbon-4 of the Thiazoline ring. This happens, because it is delocalising the negative charge that would result from its abstraction. That's exactly why the Luciferase catalyses the deprotonation that yields a Carbanion at carbon-4. This Carbanion is stabilized not only by the AMP, but also by the conjugated system to its left. Now the oxidative step happens: The carbanion attacks molecular oxygen to form Hydroperoxide.

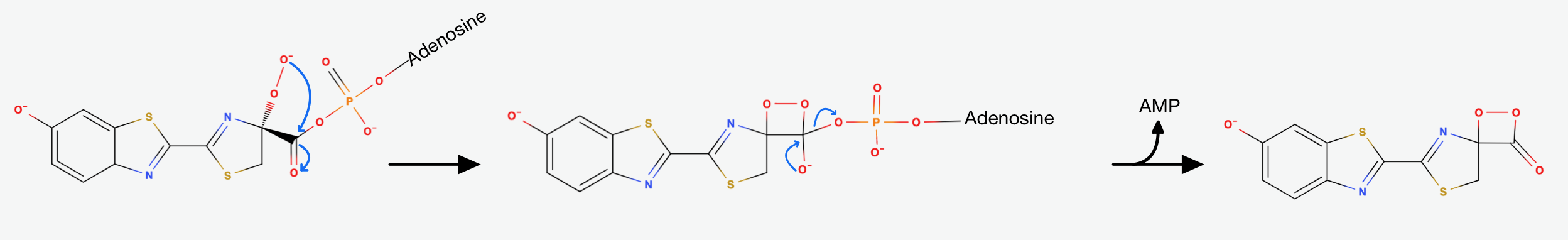

The Hydroperoxide attacks the Carbonylcarbon and they form a 4-membered ring. This is a favorable process, because of the nucleophilic acyl substitution and the loss of AMP, which is a very good leaving group. We end up with an alpha-peroxy lactone (a Dioxetanone). As I mentioned earlier: The Dioxetanone is a high energy intermediate and a conserved motif in many reactions involving Chemiluminescence. The exact mechanism of the decomposition of Dioxetanone is still in debate. The following steps will showcase one of the suggested approaches.

It is suggested that through Resonance the rightmost Nitrogen atom gets an anionic character. It can then participate in a radical reaction: The high energy Peroxide bond gets cleaved homolytically and one electron from the Nitrogen gets donated to the Oxygen on Carbon-4 so that we end up up with the diradical shown in (Fig.7) above.

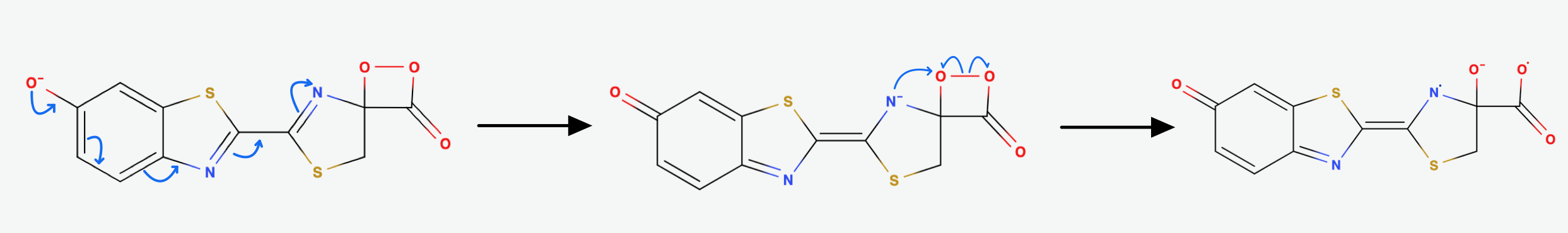

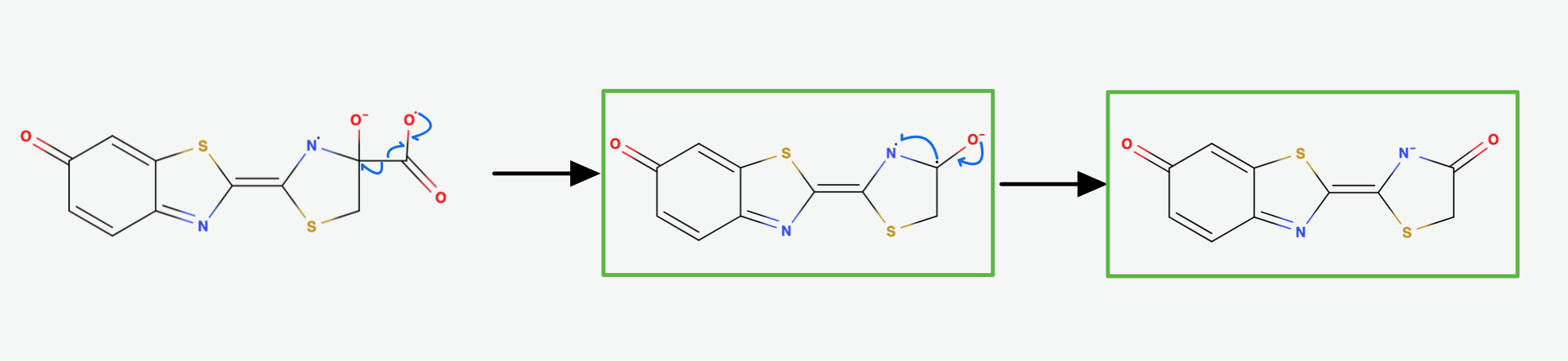

The diradical is very unstable and undergoes spontanous decarboxylation yielding Carbondioxide. Now the excited Oxyluciferin is formed. The excited state is marked by the green box in (Fig.8). The two unpaired electrons combine. The version above is the keto version but the formation of the enol version is possible as well.

Now, through some resonance, the excited version oxyanionic Luciferin gets restored. It then falls back into the ground state, emitting a photon. In this step, the bioluminescence gets produced so that our firefly can glow [5].

As we have reached the end, I hope you did enjoy your journey through this mechanism and that it left you just as much in awe as it left me.

Credits

[1] Bai, H., Che4n, W., Wu, W., Ma, Z., Zhang, H., Jiang, T., Zhang, T., Zhou, Y., Du, L., Shen, Y. and Li, M., 2015. Discovery of a series of 2-phenylnaphthalenes as firefly luciferase inhibitors. RSC advances, 5(78), pp.63450-63457.

[2] Branham, M., 2005. How and why do fireflies light up. Scientific American.

[3] Lloyd, J.E., 1975. Aggressive mimicry in Photuris fireflies: signal repertoires by femmes fatales. Science, 187(4175), pp.452-453.

[4] Marques, S.M. and Esteves da Silva, J.C., 2009. Firefly bioluminescence: a mechanistic approach of luciferase catalyzed reactions. IUBMB life, 61(1), pp.6-17.

[5] National Center for Biotechnology Information (2022). PubChem Compound Summary for CID 92934, Firefly luciferin. Retrieved August 28, 2022 from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/92934.

[6] Baldwin, T.O., 1996. Firefly luciferase: the structure is known, but the mystery remains. Structure, 4(3), pp.223-228.

[7] Cummings, C. (2019) Opiod Peptides [Online]. Available at: https://sites.tufts.edu/opioidpeptides/opioid-receptor-binding-assay/luciferase-mechanism [Accessed 23 August 2022].

Interactive Models are created using:

Nicholas Rego and David Koes

3Dmol.js: molecular visualization with WebGL

Bioinformatics (2015) 31 (8): 1322-1324 doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu829